Investigation: Ruqaya Al-Abadi ♦ Interviews and Photography: Nabiha Al-Taha

Over the past decade, poultry farming in Syria has faced mounting challenges, ranging from rising production costs and price fluctuations to intense competition from imported poultry and meat. According to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), this sector, the primary and most economical source of animal protein, has shrunk by 60% due to increasing difficulties in securing affordable feed and dwindling pasture availability caused by decreased rainfall.

In 2023, these challenges peaked with the emergence of Newcastle disease, also known as the avian plague, a highly contagious virus causing significant poultry deaths. Combating this disease requires stringent measures, including humane destruction of infected birds, enforcing quarantine for up to 21 days, and disinfecting affected farms. Additionally, the safe disposal of dead poultry, such as burial in designated, isolated sites or incineration under veterinary supervision, is essential to prevent the spread of infection to nearby farms or environmental pollution, following standards set by the World Organization for Animal Health (WOAH).

While these measures are critical to containing the disease’s spread, they have severely disrupted production operations, forcing many farms to close and increasing breeders’ losses and challenges. The situation has worsened with the spread of other diseases, such as Infectious Bronchitis (IB), commonly known as bronchitis, which has intensified due to rising temperatures.

Over the past few months, this investigative team has examined the impact of rising temperatures on Syria’s poultry sector and how this has led to increased mortality rates in some farms. The investigation also highlights the role of low-quality imported vaccines and the conditions of poultry transport through the Syria-Turkey border crossings, which lack adequate health monitoring measures.

The investigation reveals the first appearance of the avian plague in Syria, along with the failure to report the spread of this highly contagious disease to the World Organization for Animal Health (WOAH). This omission occurred despite public statements from WOAH’s representative in Syria, Dr. Basem Mohsen, who confirmed cases of infection in poultry farms across several Syrian provinces.

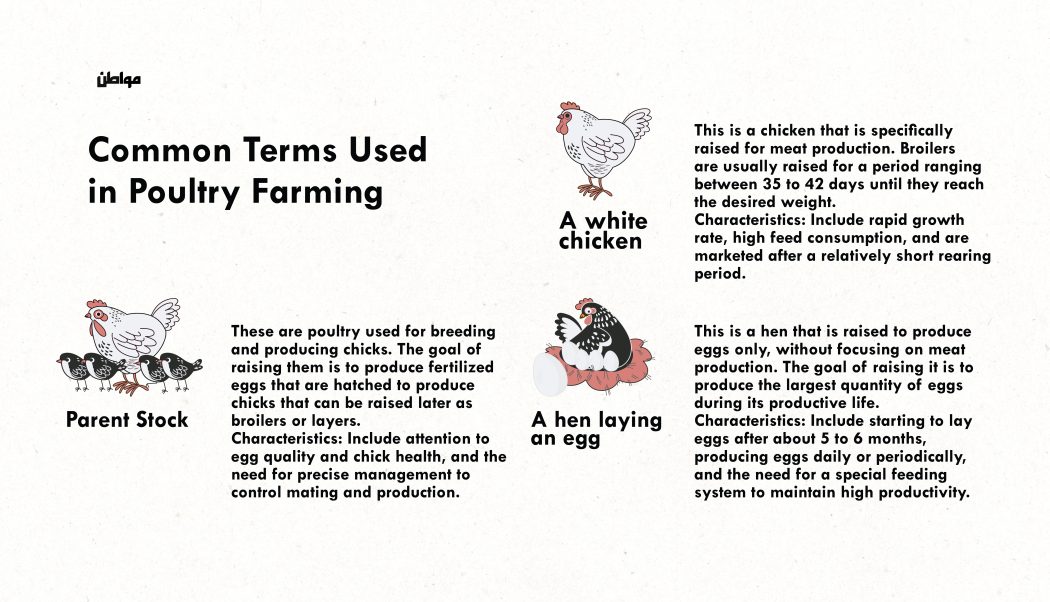

Before diving into this investigation, it is essential to understand the terminology used in poultry farming. While preparing this report, we initially faced challenges in comprehending all the farming and production methods terminology, so we clarified them with an infographic to facilitate following the details.

War and Rising Costs Shut Down Poultry Farms

In the village of Al-Kasra, west of Deir Ezzor, only seven out of sixty-five poultry farms remain operational, with all others shutting down due to feed shortages and lack of support, according to poultry farmer Hamad Al-Jadoua in rural Deir Ezzor, northeastern Syria.

Al-Jadoua adds, “The dire situation facing regional poultry farmers has become extremely challenging. With rising production costs and the absence of government and non-government support, the continuity of our work is severely threatened. There is no support at all; we are forced to buy clean water and diesel to run generators, in addition to veterinary medicines and feed, which have become prohibitively expensive.”

Similar to other provinces, the war has been a primary cause of damage to the poultry sector in northeastern Syria. This impact has affected infrastructure and breeders’ ability to purchase and raise poultry. According to Abdullah Al-Hamad, the primary supervisor of the poultry sector, the number of operational poultry farms in Raqqa, Deir Ezzor, and Al-Hasakah has sharply decreased from three thousand to barely 200 farms due to losses driven by rising breeding costs.

In April 2024, the state-owned newspaper Tishreen reported that the Hama Governorate had 400 licensed poultry farms and 24 unlicensed ones, citing the Director of Agriculture in Hama, Engineer Ashraf Bakir. These farms include broiler farms, layer farms, and parent stock farms. Bakir explained that over 45% of these farms have ceased production due to the high cost of feed and the rising prices of veterinary medicines and supplies.

This situation is mimicked in northern Syria, where poultry farmers in the city of Al-Bab and its countryside face the same challenges. Saeed Mahmoud Al-Jabli, head of the Poultry Association, stated: “The city of Al-Bab and its countryside used to be the backbone of the poultry sector. We supplied Aleppo and the entire eastern region of Syria, including Al-Hasakah and Qamishli. Everyone relied on us for poultry farming.”

He added: “In 2019, we had 2.5 million layer hens and 3 million broiler chickens. Today, we’ve reached a point where only 500,000 birds are being raised in Al-Bab. Farmers have shut down their farms due to the high costs of production, especially feed prices.”

Data from the Ministry of Agriculture and Agrarian Reform under the Syrian government indicates a significant decline in the number of poultry farms in Syria over the past decade. The number dropped by 13% in 2014 compared to 2013 and continued to decline by 1.7% in 2022. Additionally, the total poultry population has decreased by more than 70% since 2011, with a sharp 31% drop recorded in 2022 compared to 2021.

Poultry Deaths Due to Heat

Climate change further exacerbates the challenges facing Syria’s poultry sector. With summer temperatures soaring to 43 or even 45 degrees Celsius, poultry farmers struggle to keep their birds alive and maintain operations on their farms.

Hamad Al-Jadoua, a poultry farmer from rural Deir Ezzor, explains that the extreme heat intensifies the already tricky situation, especially because modern cooling equipment is lacking. Al-Jadoua says, “I need to lower the temperature inside the farm to 27 degrees Celsius, but no matter how hard I try, I can’t.”

Al-Jadoua relies on basic methods like spraying water, as he cannot afford cooling pads and ventilation systems due to their high costs. He adds, “Modern cooling pads cost around $1,500, while a ventilation fan costs $375. Given our current circumstances, we simply can’t afford such equipment.”

Hamad’s struggle is not an isolated case but reflects a widespread reality faced by poultry farmers in Syria. Dr. Abdullah Al-Hamad, a veterinarian and former head of the Veterinary Association, as well as a supervisor of the poultry sector in northeastern Syria, told the investigative team: “The high temperatures in poorly equipped poultry farms cause heat stress in birds, leading to the spread of viruses and mortality rates of up to 70% among broilers being raised.”

A 2023 study by Purdue researchers argued that heat stress poses an increasing threat to the poultry industry. The researchers recommended developing comprehensive strategies to improve management practices, such as better ventilation, optimized poultry farm designs, and adjusted bird densities, to enhance thermal comfort and reduce the heat burden on poultry.

In June 2024, temperatures reached unprecedented levels, with the European Copernicus Climate Change Service classifying the month as the hottest ever recorded. According to Syria’s General Directorate of Meteorology, the country experienced a significant rise in temperatures, ranging from 3 to 5 degrees Celsius above normal levels.

World Bank data from recent years highlights a general trend of increasing maximum summer temperatures in Syria. The years 2023 and 2024 saw notable temperature spikes compared to previous years, heightening the risk of heat stress incidents.

Amid these harsh conditions, the Directorate of Livestock under the Autonomous Administration in northeastern Syria issued warnings via its Facebook page on June 20, 2024. It emphasized that heat stress significantly threatens poultry health, resulting in substantial production losses.

Dr. Basem Mohsen, Director of Animal Health at the Syrian Ministry of Agriculture, told the local Athr Press website on June 8, 2024, that “the extreme rise in temperatures during the past period has caused the death of a significant number of birds in the region.” He added that the average rate of poultry deaths ranges between 7 and 8 birds per day, but the situation becomes abnormal and alarming when the number exceeds 100 per day.

Although there are no precise or official statistics on the number of poultry deaths caused by heatwaves in Syria recently, Dr. Sami Abu Dan, General Director of the Poultry Corporation under the Syrian government, estimated that mortality rates in some farms reached 70% in 2023.

Fragile Poultry Prone to Diseases

The pressure of harsh environmental conditions leads to poultry deaths from extreme heat. It weakens the birds’ immune systems, making them more susceptible to epidemic diseases like Newcastle Disease (avian plague). Its impact has worsened significantly in Syria as heat stress incidents have increased.

In northern Syria, particularly in the city of Al-Bab and its countryside, poultry farmers face immense challenges. They suffer massive losses due to diseases, soaring temperatures, and the high costs of energy and feed. Hasan Al-Harkoosh, owner of “The Poultry World” farm and a distributor for an industrial company in northwestern Syria, previously raised about 100,000 to 150,000 birds. Today, that number has dwindled to approximately 50,000.

Al-Harkoosh says: “I’ve lost more than one poultry farm due to diseases. Some farms had 10,000 birds, others 15,000 or even 20,000; these are significant losses.” He adds, “A large percentage of the facilities have shut down, with only about 50% still operational. Out of every ten facilities, only four remain active.”

In rural Deir Ezzor, northeastern Syria, poultry farmer Hamad Al-Jadoua shared his experience: “I suffered massive losses when broilers on my farm contracted bronchitis. This led to the death of 50 to 80 birds daily, and over a month, I lost about 2,300 birds.”

Despite the challenges posed by bronchitis, scientifically known as Infectious Bronchitis (IB), it is not the only threat facing Syria’s poultry sector. According to Dr. Abdullah Al-Hamad, a veterinarian and former head of the Veterinary Association in Deir Ezzor and a supervisor of the poultry sector in northeastern Syria, the industry experienced a major disaster in 2023 due to the spread of Newcastle Disease (avian plague), which caused mortality rates ranging from 50% to 70% in every affected farm.

On February 20, 2024, the state-owned Tishreen newspaper quoted Dr. Basem Mohsen, Director of Animal Health at the Syrian Ministry of Agriculture, saying: “In early September 2023, the region experienced unprecedented temperature spikes, causing heat stress in birds. This stress broke the immune defenses of some birds, leading to suspected cases of Newcastle Disease (‘pseudo-plague’) among certain farmers.” He explained that poor farm biosecurity, low-nutritional-value feed, vaccines of unknown origin, and farmers’ neglect of timely vaccination schedules—particularly for vaccines like the Newcastle-Gumboro-Bronchitis variant—contributed to the worsening situation.

According to a scientific study published on the National Library of Medicine website on April 21, 2024, titled “Stress and Immunity in Poultry,” heat stress reduces feed intake and growth in poultry, weakens immune responses and vital functions, and increases the risk of diseases.

Where Did Newcastle Disease First Appear?

According to a local North Press website report, Newcastle Disease (avian plague) first appeared on February 26, 2021, in the Jel Agha (Jawadiyah) area in rural Qamishli, northeastern Syria. The report featured videos and images of poultry deaths, and one farmer noted a loss of appetite among the birds; he used to feed them nine bags daily but observed a decrease of about seven bags per day—an early indicator of Newcastle Disease.

On April 10, 2021, the Director of Agriculture in Al-Hasakah Governorate, Engineer Rajab Salama, told the SANA news agency that poultry infections with Newcastle Disease were “within normal limits” when the disease spread in Syria.

Although Newcastle first appeared in northeastern Syria two years earlier, no virus cases were recorded in 2022 across Syria. However, the virus re-emerged in June 2023. Numerous government and non-government reports highlighted poultry deaths attributed to Newcastle Disease, allegedly originating from Turkey.

In this context, the World Organization for Animal Health (WOAH) reported the first highly pathogenic avian influenza (H5N1) case in Afyon Province, western Turkey, on January 31, 2023. According to the organization’s report, the Bornova Veterinary Control Institute analyzed samples from infected birds, confirming their infection with the virus.

The organization stated that a protection zone with a radius of 3 kilometers and a surveillance zone with a radius of 10 kilometers were established around the outbreak area. Epidemiological monitoring and testing measures were implemented in these zones, and poultry culling continued to prevent the spread of the virus. The case remains under monitoring, indicating that complete control over the outbreak has not yet been achieved.

Although both H5N1 and Newcastle Disease (NDV) are infectious diseases that may be linked to commercial poultry farming and the movement of wild birds (such as pigeons in the case of Newcastle and waterfowl in the case of H5N1), the two viruses belong to different viral families.

Thijs Kuiken, a comparative pathology scientist at Erasmus University Medical Centre in the Netherlands, told the investigative team: “Newcastle Disease Virus (avian plague) belongs to the Paramyxoviridae family, while the H5N1 virus belongs to the Orthomyxoviridae family. Therefore, H5N1 can’t mutate into Newcastle Disease, just as a domestic cat (family Felidae) can’t turn into a wolf (family Canidae).” Thus, he added, “the source of the Newcastle Disease outbreak among local poultry in Syria must be sought elsewhere.”

WOAH Denies Reporting Newcastle Disease

The investigative team emailed the World Organization for Animal Health (WOAH) to inquire about recent reports of Newcastle Disease cases in Turkey or Syria, particularly since Dr. Basem Mohsen, the Syrian government’s director of animal health, serves as Syria’s official delegate to the organization.

WOAH responded that neither Syria nor Turkey had reported Newcastle Disease outbreaks to the World Animal Health Information System (WAHIS) in 2024. The organization clarified that the last reported outbreak of Newcastle Disease in Turkey occurred on August 7, 2006, and was contained by January 9, 2007. Furthermore, WOAH confirmed that Syria had never previously reported any Newcastle outbreaks.

When the investigative team asked the organization why their delegate had not reported Newcastle cases, WOAH responded: “We have re-verified and found no notifications regarding Newcastle Disease from Syria through the WAHIS system. Syria reported being disease-free during the second quarter of 2023.”

This is despite multiple public statements made by Dr. Basem Mohsen to several Syrian government media outlets, including the SANA news agency, confirming cases of Newcastle Disease in Syria and reporting poultry deaths. According to the WOAH’s Wildlife Health Law, Article 10.9.2 requires reporting suspected cases of Newcastle Disease.

On September 4, 2024, before this investigation was published, WOAH sent an email updating the information about the spread of Newcastle Disease. The email stated: “After communication with authorities in Syria, it was confirmed that the rise in poultry deaths was linked to increased levels of mycotoxcins in poultry feed, coinciding with heat stress caused by the heatwave that struck the country in August 2023.”

The investigative team reviewed statements by Dr. Basem Mohsen in the media regarding increased levels of mycotoxcins in poultry feed but only found two reports: one published in Tishreen newspaper on February 20, 2024, and another on the Khabeer Souri website on February 26, 2024. In both reports, Dr. Mohsen mentioned that “low-quality feed contributed to the spread of disease and the deaths of large numbers of poultry.”

From a scientific perspective, the impact of low-quality feed on poultry health differs from that of mycotoxcins. Low-quality feed causes gradual malnutrition, which weakens the immune system and makes birds more susceptible to diseases such as Newcastle Disease. According to a scientific study titled “The Impact of Heat Stress on Poultry Health and Performances, and Potential Mitigation Strategies,” published in MDPI on July 24, 2020, poultry fed on imbalanced diets lacking essential elements needed for metabolism and immunity are more likely to die without appropriate intervention.

In contrast, mycotoxcins in feed, such as aflatoxins and fumonisins, directly poison poultry’s vital organs, including the liver and immune system. These toxins are produced by fungi growing in improperly stored feed. Even without environmental factors like heat stress, mycotoxins can cause rapid mortality due to their toxic effects. This was corroborated by another study titled “Treatment Strategies for Mycotoxin Control in Feed,” published in the Journal of Animal Science and Biotechnology on January 28, 2022.

Poor Storage of Imported Vaccines

Amid escalating health challenges faced by poultry farmers in Syria, questions are rising about the role of imported vaccines in combating diseases, especially under harsh environmental conditions and the spread of illnesses such as Newcastle Disease and Infectious Bronchitis (IB).

Hamad Al-Jadoua, a poultry farmer in Deir Ezzor, northeastern Syria, states: “Farmers in my area rely on offices affiliated with industrial and commercial companies that supply feed, chicks, and veterinary drugs imported from Turkey.” However, the quality of these drugs is often poor, with counterfeit or spoiled medications frequently smuggled into northeastern Syria after expiration dates are altered due to a lack of effective pharmaceutical oversight.

Abdullah Al-Hamad, a former head of the Veterinary Union and current supervisor of the poultry sector in northeastern Syria, confirms: “Vaccines imported from Turkey, through the Kurdistan Region, or smuggled from Jordan have at times exacerbated health problems instead of solving them.”

He adds, “Sometimes vaccines arrived spoiled due to improper storage (not adequately refrigerated), which led to rapid disease outbreaks.” Poultry mortality rates from epidemics have reached alarmingly high levels in regions under the Autonomous Administration’s control: 60% in Deir Ezzor, 50% in Al-Hasakah, and around 30% in Raqqa and Manbij, according to poultry sector officials.

Meanwhile, veterinarian and farmer Mohammed Al-Gharqan from Idlib, northwestern Syria, notes that importing vaccines without strict oversight has also caused disease outbreaks. Al-Gharqan states: “Some people import vaccines for profit without considering their quality, leading to the spread of diseases.”

Recognizing the importance of vaccines in curbing disease outbreaks, the investigative team researched imported vaccines used to treat Newcastle Disease and Infectious Bronchitis. By reviewing social media accounts of industrial companies in northwestern Syria, the team obtained photos of these vaccines on the Facebook page of Al-Marai Company in Idlib and its countryside, confirming that local farmers use these same vaccines and pharmaceutical brands.

According to its website, the team investigated the manufacturer of these vaccines, Ceva Santé Animale, a French company ranked as the ninth-largest veterinary pharmaceutical group in the world. The verified products included four specific vaccines.

The team also spoke with representatives from industrial companies importing veterinary drugs to understand the import and transportation process, especially during high-temperature periods. Hasan Al-Harkoosh, a farmer and distributor for “Om Al-Qura,” one of the largest poultry companies in Al-Bab, northern Syria, which distributes to various parts of Syria, stated: “We buy veterinary drugs through Turkish traders. Shipments are transported through border crossings (Al-Rai, Bab Al-Salama) using trucks or vehicles not equipped for transporting drugs and lacking refrigeration units.”

According to pharmaceutical instructions on the manufacturer’s official website, these vaccines must be stored at temperatures between +2°C and +8°C and protected from light. The company also specifies that some vaccines must not be frozen to ensure efficacy. This storage requirement does not align with the transportation methods described by Hasan Al-Harkoosh.

A study published in October 2009, “The Effect of Storage Conditions on the Potency of Newcastle Disease Vaccine La Sota,” examined the Newcastle Disease (La Sota) vaccine stored under power outage conditions. It reported a significant decline in vaccine efficacy when stored improperly; the vaccine’s potency decreased from 128 before storage to just eight after 140 days, indicating a sharp loss in effectiveness.

The investigative team emailed the pharmaceutical company several times to inquire about the quality of vaccines available to farmers in Syria. Still, a response was received after the publication of this investigation.

Imported Broiler Breeding Stock

In addition to the challenges posed by imported vaccines, poultry farmers in Syria face another issue related to importing broiler breeding stock from Turkey. It is believed that the imported birds may be a source of disease outbreaks.

Mohammed, a poultry farmer in his 30s from the village of Al-Ajmi, east of Al-Bab in rural Aleppo, has been raising poultry for 15 years. Mohammed, like other farmers, has suffered significant losses during this time. He attributes approximately $25,000 in losses over just 20 days to the spread of diseases on his farm. Mohammed states: “One of the reasons that contributed to the disease outbreaks on my farm is the importation of broiler breeding stock from Turkey.”

On June 2, 2024, the head of the Poultry Association in Al-Bab and its countryside sent an official letter to the local council and the director of agriculture and animal health in Al-Bab. The investigative team obtained a copy of the letter, in which the association head called for “activating local oversight of broiler chicken and egg products.” The letter highlighted the spread of epidemics that have led to disease outbreaks in the poultry sector and warned of an impending health catastrophe in northern Syria.

Saeed Mahmoud Al-Jabli, head of the Poultry Association in Al-Bab and its countryside, explained that the problem lies in the fact that chickens imported from Turkey are at the end of their breeding cycle and carry numerous diseases. He added: “We don’t have the vaccines needed to deal with them. We’ve asked all concerned parties, including the Chamber of Commerce, for help, and while there has been some response, the situation remains dangerous and requires urgent intervention.”

According to data provided by Abdul Hakim Al-Masri, Minister of Economy in the Syrian Interim Government, “The total import of live chickens from Turkey via the Al-Rai and Bab Al-Salama border crossings during the first half of 2024 amounted to approximately 14,106 tons, with 7,861 tons re-exported internally to areas under the Autonomous Administration in northeastern Syria.”

Data from the United Nations trade database indicates that Turkey’s exports of live poultry to Syria have increased by 44.8% over the past decade, with net weight rising from 1,069.769 tons in 2014 to 1,550.061 tons in 2023.

The Impact of Heat Stress on Poultry Transport

According to a study by M.A. Mitchell and P.J. Kettlewell for the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), thermal challenges such as extreme heat or cold are the primary threats to bird welfare during transport. Prolonged food and water withdrawal and exposure to vibrations and accelerations during transit can exacerbate heat stress, increasing mortality rates during transport, particularly under harsh weather conditions.

Poultry transport is unavoidable in livestock farming, whether for transferring birds to other farms, markets, fattening facilities, or slaughterhouses. Journeys can last up to 48 hours without providing the necessary water or feed. Transport typically occurs in open trucks exposed to the elements, adding to the animals’ suffering, especially in summer when temperatures sometimes exceed 40°C.

The investigative team attempted to film at the Al-Rai and Bab Al-Salama border crossings to understand better how live poultry is transported between Syria and Turkey. However, the border management denied permission to film. Attempts to reach import companies for detailed insights about their operations were also met with a need for more cooperation regarding filming.

However, the team obtained a video from Hasan Al-Harkoosh, a poultry farmer and owner of “The Poultry World” shop in Al-Bab. The undated video shows hundreds of live chickens (broiler breeding stock) crowded in plastic crates inside an open Turkish truck under the midday sun. When explained the truck’s destination and the transportation method under such conditions, Al-Harkoosh explained: “The truck was coming from Turkey via the Al-Rai crossing heading to northern Syria. They always transport shipments this way, spraying water on the chickens to keep them active.”

Weak Oversight at Border Crossings

Many poultry farmers in northwestern Syria complain about inadequate oversight of imports from Turkey, especially amid epidemic diseases. The border crossings between Turkey and Syria are controlled by various parties on the Syrian side, necessitating an understanding of the regulatory practices at each crossing.

There are veterinary testing labs in northwestern Syria at the Bab Al-Hawa crossing, but this oversight’s effectiveness still needs to be improved. Dr. Abdel Hai Al-Youssef, head of the Animal Health Department in the Salvation Government—the de facto governing authority in Idlib—confirms that health monitoring is in place but faces significant challenges.

According to Dr. Al-Youssef, efforts are being made to simplify the oversight process by reducing the procedural burden, especially for imported items like chicks from Turkey. He explains that advanced veterinary analyses, such as BSR and immunological testing, are prohibitively expensive, increasing farmers’ financial burden. Consequently, simplifying the regulatory process becomes a preferred approach.

When asked about health oversight at the Bab Al-Salama crossing, Abdul Hakim Al-Masri, Minister of Economy in the Syrian Interim Government, stated: “We do not allow any material to enter without testing, regardless of its source. Even if the materials come from relief organizations and are distributed for free, we test them more rigorously than traders’ imports.” He added: “Currently, we test a significant portion of materials in laboratories in Turkey. While some labs exist here, they are insufficient.”

Saeed Al-Jabli, head of the Poultry Association in Al-Bab and its countryside, highlighted the repercussions of inadequate oversight. “The lack of thorough testing for imported products allows non-compliant materials to enter, directly contributing to disease outbreaks among poultry and increasing farmers’ losses,” he said.

Al-Jabli added: “We have demanded the application of health controls on products entering through the crossings, but unfortunately, the Chamber of Commerce does not give this issue the attention it deserves.” He also noted: “We have spoken to Turkish traders and requested the installation of health inspection equipment at the crossings or the requirement that products enter only with a health certificate approved by us, not solely by the Turkish side.”

Despite the growing threats to Syria’s poultry sector—ranging from climate changes and deadly diseases to inadequate import controls—farmers continue to face substantial losses. As diseases spread unchecked due to ineffective monitoring, How can this sector survive amid these escalating challenges?

This investigation is published in collaboration with Nawa Media.